Speaker So what what is best known for but what, in fact, is the truth?

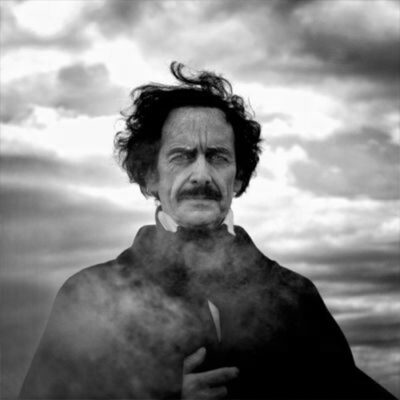

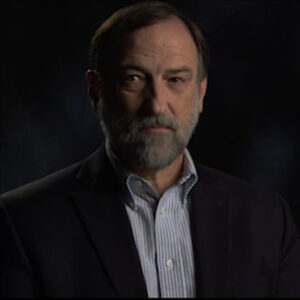

Speaker Well, DPO is best known for his tales of horror and he is associated with Halloween. But in fact, he wrote a breadth of genres and was very proud of his versatility, his virtuosity. He invented the detective story. He wrote Tales of Rassi in a situation that we are still honoring today. He wrote lyric poetry. He wrote a play. He wrote the greatest criticism of his age. He wrote science fiction. He wrote fantasy. He was a man of many talents, a writer of many skills. And it was important to him that that be recognized.

Speaker Thank you to you. And if you don’t, this is fine. Do you have the numbers at hand that you could say he wrote over 70 poems and 20 tales and I would be afraid of getting it wrong.

Speaker I think you wrote about 70 tales, but if it’s 80, I just. Yeah, OK, that’s.

Speaker What is that? Again and again, kind of briefly, because these are statements we’re hoping to have in this kind of montage at the beginning of the film.

Speaker So what is the difference between the general popular view of the dark demanded, perhaps opium addicted PO and the real man, Edgar Allan Poe?

Speaker When I visited an elementary school class, I was asked questions by the students, and the first question was how many people did Poe really kill? Well, you know, there is a tendency to presume that Poe is the characters he writes about, and therefore one infers that Poe was a murderer, was, you know, a drug, a drug addict, that he was a maniac, various sorts. He did have his eccentricities and his problems. He did specifically have a particular problem with alcohol. That’s true. But he was not a drug addict. He didn’t take drugs except for one time when he made a half hearted effort to kill himself with laudanum.

Speaker But other than that, he was not a drug user. I think that people tend not to see the humanizing elements of Poe because we want this fellow to be as wild and crazy as possible. But in fact, who could have lasted at that pitch of intensity and darkness? He had his light moments. He had his happy moments. He had his social world. He had people who loved him. This was a man who, out of the sight of the public, lived a calm and very disciplined, disciplined life. Otherwise, he couldn’t have written all this incredibly carefully crafted, hermetic work.

Speaker Great, thank you.

Speaker Why do you think it’s important for this image of power to survive? I mean, why does the culture, our culture, our readers, our our young people, why do they hold on to this myth about power?

Speaker I think caricature is easier to manage. And that goes with regard to many people. If if we think of Marilyn Monroe, we think of a specific aspect of Marilyn Monroe, not the full person she was or John Wayne or any number of very famous people. But there was a complexity, I’m sure, with Marilyn and John Wayne and with Paul.

Speaker There was a complexity and perhaps we need him to be the the character he portrays in his tales of horror.

Speaker But if we truly love him, we will see other sides tender, sweet, quiet, domestic, and that enriches our appreciation for what he was able to do with all his writing.

Speaker Thanks. Thanks. I’m cutting you off sort of mid chest and the gestures are nice, but if you could gesture higher, that would be great.

Speaker You know, boy, I don’t know how I suggest a compromise when you should a little wider.

Speaker I will, but I can’t get the way. It’s too late. OK. All right.

Speaker So how high is visible like here? Yes.

Speaker OK, I don’t know if I’m going to do whatever and then because remember, we can always punch in.

Speaker So. Yeah, um. OK, this is good. Thank you.

Speaker The early appropriation of power, I mean, one of the earliest motion pictures I forgot the year was made about is called The Raven, but it was really sort of a biography of power.

Speaker I mean, why is it that artists of all genres of media have appropriated power almost from the start? What what does he why is he so inviting?

Speaker Well, his life was unusual also. His image is immediately recognizable. So and that is not true for many authors. How many authors lead a less dramatic life and have countenanced it less immediately recognizable with Poe? You have a face that everybody knows, probably everybody remembers from their childhood when they first read Poe.

Speaker And then there is the story of his life, which is as interesting as the stories that he wrote.

Speaker So an artist, moviemaker and a writer poet, a dramatist, would be attracted to this fellow whose work is extraordinary and whose life is extraordinary. And that artist would have the possibility of allowing the resonance of the work and the life to enliven the work of art and children.

Speaker Who you and you had talked about this before. What why is he unique among?

Speaker Well, I was talking to a teacher once who said Poe is the first great writer and people get as children. And so whether it’s perhaps Annibale or The Raven or The Tell-Tale Heart, in my case, it was the goldbug.

Speaker We understand enough to be satisfied in a way that we couldn’t understand Melville or Hawthorne or Thoreau. I’m talking about the age of 10, the age of 12. And in our adult years, we look upon Poe with some fondness for that very fact that he was accessible to us when we were kids.

Speaker I think that’s an amazing feature of his. And in fact, when I organized a conference in Richmond in 1999 and got a submission on Poe for the 90s.

Speaker I said, well, OK, poll for the 1990s, this was 1999, but now it was polled for people in their 90s who wanted to reread this guy whom they loved when they were kids back towards the beginning of the century. So I think that’s something I always got going for him. We all remember him when.

Speaker That’s great. That’s nice.

Speaker I’m going to you know, I know I sent you a lot of biographical questions, but we kind of covered a lot of that with other people to do it fits into a little help.

Speaker Talking about the adolescent Edgar, when Jane Standard dies, when his is obviously he’s lived with the death of his mother. I think Fannie Allen was always a little unhealthy. What was how was he taking on board this kind of omnipresence of death and not just in his own life, but in culture of death, a culture of mourning that was in America at the time for obvious reasons? How is that affecting him? And the more you can sort of speculate and within your comfort zone about how he must have felt or what it must have seemed like to him, imagine him walking through Shockoe Cemetery and what was he feeling? What was he thinking? How was that shaping him?

Speaker Well, he indeed did go to the cemetery when Jane Steve Stanton died. There is a recollection of his lying on her grave. She was someone who would listen to him, to whom he could confide, as he could not at home, particularly had a difficult relationship with John Allen. And this. Warm, gentle, thoughtful, interested woman. Served, I’m sure, as an embodiment of what he would have imagined his mother to be had she still been living. So her death reinforced the sense of loss that he had at the at the death of his mother. He was almost three. We don’t know exactly what he remembered, but certainly he would have remembered some sort of loss.

Speaker And that was compounded by the death of his brother when he was when he was a little older, 18, 31. So he was 22, a death he would have witnessed so that people would have certain frisson. Seeing or walking through a cemetery is understandable, given the intense losses he had early on of people whom he loved. The culture of mourning intensified his perhaps his responsiveness to that loss. He knew that there was a market place for this kind of writing, but it wasn’t purely for the pecuniary reward that the sadness was of his soul. And he recognized that there was an audience out there who shared that sadness.

Speaker Let me ask a little more about that.

Speaker So when do you see him starting to show some canniness or at least some awareness of market forces in the literary marketplace?

Speaker Well, I would I would point to about 18 30s. Paul had been writing poetry. Three books of poetry, starting with Tamburlaine in 1827 and his career wasn’t really taking off, the books of poetry were not great successes. Much as we highly regarded them today in their own time, they garnered a few good reviews, but they were not and they were not stirring up a storm. So when he realized this in eighteen thirty five about and he had been writing fiction and it’s the shift to fiction that gave him the fame, although of course we celebrate his poetry. But within his life it was that shift that enabled him to win wider attention. Manuscript found in a bottle won an award in 1833. He was able to get a job as an editor of the Southern Literary Messenger. In eighteen thirty five, he won another award with the Goldbug in eighteen forty three. His detective stories were great successes in the early eighteen 40s, so I think that was very canny of him to shift from the poetry to the fiction and then return with The Raven, with Annabel Lee, with Elderado, because he’d already built up this tremendous interest in the audience for his fiction and his criticism.

Speaker Of course, great things going back to that first when he first makes the shift with a manuscript found in a bottle.

Speaker How can you describe what a big break that was for him and how he must’ve felt when finally he got recognized by winning that prize?

Speaker Well, he would have been just delighted. He had submitted stories to the Philadelphia Saturday Courier and they did not win the prize, but they were published without his name. So he must have been somewhat disappointed, maybe even a little discouraged. But with the winning of the prize for manuscript found in the Bible, I think he would have been elated and would have thought yes. This is what was supposed to happen. Finally, it has happened, it was managed to find a bottle is a detail. It’s based on the story of the Flying Dutchman. And it is.

Speaker Supernatural and intense and memorable as opposed stories are, and he even embeds himself in the story when he describes the captain of the Flying Dutchman.

Speaker It’s a fellow who looks remarkably like Edgar Allan Poe. So he’s beginning to build that link between his life and his work and those who would recognize that would have gotten an extra pleasure from it.

Speaker Can you describe that very sad letter he wrote to Ken Kennedy saying that he couldn’t get.

Speaker Yes as well. So when he won the award for manuscripts out of the bottle, he got to know a little bit anyway, the members of the committee who had selected the story and one of them was this fellow, as you mentioned, Kennedy, John Pendleton, Kennedy, who invited him to dinner. And Poe declined because he did not have clothes to wear.

Speaker Fine enough clothes to wear to dinner, and this, I think, very much touch Kennedy and he provided money to PO. He provided Poe with the connection to Thomas White, the editor of the Southern Literary Messenger proprietor, and he was encouraging, as you can see, in letters to Poe and helped get him started, as John Neal did, as several others did early on. And I was always grateful.

Speaker Great. Thanks. Yeah. Such a sad poem. Yeah. So can you describe the novel?

Speaker What kind of novel is it? Is it how does it incorporate autobiographical aspects and how is it a kind of novel within a novel?

Speaker Is that a precursor of more modernist novels in some way?

Speaker Well, Pym is a CEO for readers. At the time, it would have probably appeared to be something like Robinson Crusoe, which would have been deliberate on this part.

Speaker However, in the case of this novel, the horn was when it started again. Yeah, just I think yeah.

Speaker I mean, this is a question to which I could offer a longer answer. Is that OK or not.

Speaker Well, shorter is always better or in pieces. You know, if we could just do it in pieces because that makes it easier for us because the way we’re going to do this is we’re going to have some few readings, very brief. But yeah, if your readings from them ends up speed, what was the name of those posts? First and only novel.

Speaker When did he write it? When was it published and what? In a very general way, what kind of novel was that?

Speaker Paul was working on the narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym while he was living in Richmond 1836, and it was early chapters were published in the Southern Literary Messenger in January and February of 1837. He kept working on it even when he had moved to New York City. And in 1838 it was published by Harper and Brothers. It’s a C novel it would have seemed to readers at the time, something akin to Robinson Crusoe.

Speaker Except as you get into the later chapters, what had been plausible becomes implausible, then impossible, then outright unbelievable.

Speaker And in fact, in the British first edition, the final paragraph was removed because it was just thought to be. Beyond anybody’s imagination, but I think that final paragraph is, in fact, the greatest strength of the novel.

Speaker How does it incorporate a few autobiographical aspects?

Speaker He has 25 chapters. The middle chapter, Chapter 13 covers two weeks and 22 paragraphs. One weekend, 11 paragraphs in the character who is analogous to his brother Henry. The character’s name is Augustus dies on August 1st, as Henry actually did in 1831.

Speaker So it’s a novel memorializing the death of his brother, who creates a ship on either side of the novel first and last chapter. The name of the ship is The Penguin, and he says that the singular characteristic of a penguin is its spirit of reflection, and thereby, I believe he has created that image of facing mirrors, which creates the infinite reflection of whatever is at the center. And what is at the center is the death of his brother. So there thereby in 1838, seven years ahead of the Raven, he has already embodied what he said. The Raven was about mournful, a never ending remembrance.

Speaker Is it a reflection somehow? Do you do you see reflected in a post sense of just the difficulties of his life, of poverty, of the incredible challenge of trying to be a writer? Do you see those themes?

Speaker It mostly what is reflected of his life is his family. It’s the brother who is an avenue to his mother, and that’s those two people I think are at the heart of the novel, he wrote, there is no tie more strong than that of brother for brother, not so much because they love each other as they love the same parent. And I think that. Dynamic Henry, as a conduit to allies of pope, is very much alive and well in that.

Speaker And is it a precursor of more modern novels? Was he doing things sort of story within a story in determining voice, unreliable narrator things like that that were really kind of precursors of modernism? Well.

Speaker I think you could say so in terms of his attention to structure, he was very concerned with the design of the hole and I think you see that in in James Joyce or in Virginia Woolf. And so thereby I think you could say it anticipates modernism. I think also the sense in which his writing, sometimes in him, but oftentimes in other works, blends genres so that you have in Eureka, 1848, a prose poem. That kind of gend genre bending, I think is a characteristic that you find in modernism as well. Think of the way in which Virginia Woolf has a poetic quality in her fiction.

Speaker And why don’t you think, however, wrote another novel, what maybe if you could just step back and, you know, speculate a bit about how he lead, you want to grab a seat? Did you meet? I can’t remember, Richard. OK, either way. Why didn’t he write another novel?

Speaker What do you think he discovered about the genre of the novel he wrote Pym because Harper Brothers said the market is interested in a long narrative.

Speaker So he was trying to be responsive to that. I think that his pleasure in writing fiction was in creating a singular effect upon his reader, an effect that would result from the intensity of his language over the course of one sitting. A novel is not typically read at one city, so I think he would have been a little less than happy with the lesser degree of intensity, the lesser degree of control that he had as a writer in a long narrative. So that’s why I think he returned to the short story as a way not only to compel interest in his readers, but to compel an effect that was hard to sustain over 200 pages.

Speaker I think that’s really good because you’re the first person to have really given us that kind of analysis of him in a way that I think we can use.

Speaker So can you pick an example from one of his tales, one of the earlier ones where he seems to have nailed it?

Speaker It’s like, OK, this is this is what he means when he talks about unity of effect, when he talks about all his theories of of how to make a tale work, you could pick one of the earlier ones and say by by the public, by the time he published X, we really see people beginning to master this.

Speaker Well, perhaps I could take Usher 1839, the fall house of Usher, one of his greatest tales.

Speaker It’s a Gothic tale now. He did not invent the Gothic tale, but he mastered it to the extent that we sort of imagine that he invented the Gothic tale. And this is a story of kind of the return of the repressed. This man who has lived in this house with his sister and he has.

Speaker It turns out buried her alive.

Speaker Well, the intensity of the learning of this fact and the. Dissent to the tomb of the narrator and Roderick Usher himself.

Speaker And the I’m going to have to start over. OK, great. And maybe I said something was off, so OK, maybe we could just start off by saying, you know, an 18 I forgot the date already. Thirty nine.

Speaker Thirty nine. When he publishes the fall of the house, I’m not sure we see that he’s, you know, he’s really good at.

Speaker And you know why maybe I’ll shift to Tell-Tale Heart. I think that’s a good idea. We’re going to we’re going to have to tie them. So it’s going to be so OK. Yeah. So what Tell-Tale Heart is, I think. Forty three, we can look it up. OK, so I’ll do both, OK.

Speaker What’s an example with a date of a tale where Poe really nails everything he’s aspiring to do?

Speaker This tale that comes to mind is The Tell-Tale Heart from 1843. This is a four page story, which is Memorize Bible and memorable, intense and Ceaseless. One of his classics. It’s the story of a fellow who hates an old man.

Speaker He can’t quite pinpoint the reason.

Speaker Perhaps it’s his eye and stands at the door to his bedroom, opening slightly and then ever more slightly day after day through a week so that he will not be perceived. And it is the intensity of his plan and the deliberateness and his conviction that his very deliberateness proves that he is sane when all the time, of course, he is mad. And the building of this very short story to that incredible moment when he rushes into the room and kills the old man and now has silenced the beating of his heart, he thinks. But now and when the police arrive downstairs, he still hears the beating of the heart and the intensity of the first half of the story leading up to the murder is repeated this time because he hears the heart.

Speaker The policemen don’t know what’s going on, but he believes that they do and that they’re humoring him and pretending not to hear that part, which, of course, is only in his own mind. And finally, he just confesses he cannot take it any longer.

Speaker It is the one of the great stories of guilt and of parricide, and one could readily relate it to his own very conflicted and tormented feelings towards his foster father, John Allen.

Speaker Great ally, it is a great story.

Speaker Can you talk a little bit about the fact that it doesn’t it doesn’t take place in a named city or even a named country? I don’t think the characters even have names. And yet, was he writing about America? Was he writing about urban anxiety? Was he writing about crowded neighborhoods and apartment buildings where you don’t know your neighbors?

Speaker Well, he was living in Philadelphia, but I don’t think that that fact was important to him. He wrote The World is the theater of the literary history.

Speaker He had a sense that he was a great writer on a world stage. And so I don’t think he was terribly interested in anchoring his fiction to one particular location, but wanted to it to be available to the world. In fact, in his earlier works, his settings are usually abroad. In later times they were more American, as Jerry Kennedy has pointed out. And sometimes you can see the connection precisely, for instance, in the black cat, the basement. I think it’s pretty much the basement that you see when you go to the powerhouse in Philadelphia. It’s phenomenal. But I don’t think he was always interested in revealing the specificity of geography because he wanted his work to work everywhere.

Speaker And I guess what I’m also trying to get to those was he tapping into was he putting his finger on the pulse of a new kind of anxiety in America and among his readers, did he know that he didn’t have to name a city or a place because people would feel it anyway?

Speaker Oh, yes, that makes sense. I think that there was an intensity of feeling that was available to his readership, whether they were working through their own personal dynamics or they were sensing something more of a social nature. I would point to a story called The Man of the Crowd, which is really a story of a city and a man in a city. And you have that kind of dark, anonymous force that a city. Is the home, too? It would have been, I think, harder to just take a prairie and have this kind of intense building of of emotion and of mystery as much as you can in a city. And this character is crisscrossing the city. And whether it is London or some other city, we all know a city and we can make that story our own by imagining it in the city. We know.

Speaker And you take the magazine then without getting too specific, just that, what was it like for him? What was going on?

Speaker Paul lives in Philadelphia with his wife, Virginia, and his mother in law, Maria Klam, from 1838 to 1844. This was a relatively stable period in his life. He was immensely productive. He invented the detective story there in Philadelphia and he wrote any number of other great works.

Speaker Usher, the black cat man in the crowd, the goldbug there in Philadelphia. It was a period of great productivity. Sadly, in 1842, his wife coughed up blood and this was the beginning of her illness, which was tuberculosis and probably topos utterly reminiscent of the death of his brother, Henry. So he was of a delicate disposition in any case with regard to alcohol. But now with his wife coughing and spitting up blood, this wife, whom he adored, he was rot and a friend or two would come by and say, Eddie, and off he’d go and he’d come back.

Speaker Inebriated and very sick, and he would take maybe two or three weeks to recover, and then he’d go through good, strong period of writing and his wife, his wife’s illness with sort of, I think, bring him to the brink again.

Speaker And so you had a cycle of productivity and drunkenness and collapse in the years, say, 42, 43, 44. And then he he moved to New York and he had his great peak year, 45, when the raven when the Raven came out. But still the the pain of his wife’s illness was with him and perhaps contributed to his writing a poem about the loss of a beloved because he knew he would lose her.

Speaker I think we can cut around a lot of the noise, I think the thing was, can you use that as a band and just give a little explication around it about how it was hard for him to, for obvious reasons, to really acknowledge how sick she was?

Speaker He said he she burst a blood vessel while singing. He did not write. She has tuberculosis.

Speaker No, no. But he did say and she had to someone else maybe she she had a singing accident.

Speaker Well, I think he was trying to downplay it, but he knew what was going on. I think he chose to live in lower Manhattan, not only because it was the hub of publishing, but also there was Washington Square Park. There was air that she could breathe, which was also an attraction eventually for him. He was very concerned with with good reason for her health and she wasn’t getting any better. And in early 2007, she did panic.

Speaker And how hard was it for him to acknowledge the reality of it while she was still alive?

Speaker I think it was hard. I think probably that contributed to his drinking. He wrote to someone who asked him about his drinking. He says, you make a mistake when you attribute the insanity to the drink.

Speaker You should attribute the drink to the insanity. And by insanity, he met his utter. Desperation at the unceasingly continuing illness of his wife.

Speaker Nice things. So after that, just very briefly, what was it about the Raven that made it such a hit?

Speaker It was the combination you want to start, and that was kind of loud, even I heard. Let me just look out the window. I just see curious, like, is it Reagan was his greatest hit. I’m sorry, sir.

Speaker OK. And the raven was posed greatest hit, comparing it to the goldbug. He said the bird beat the bug all hollow. This was the work that made him probably the most famous writer in the United States.

Speaker 1845. What was it? I think it was a combination of the sound, the rhythm and the theme, the theme of loss to which everybody can sadly connect. It was something that was performable. And when Poe would appear at a soiree, he would be introduced as the raven. And of course, he would recite the wreath.

Speaker And it was so hypnotic that nevermore and the unmerciful disaster followed fast and followed faster that sense of inexorable building, as I mentioned, with regard to The Tell-Tale Heart, so that it was known and now people are listening to it and sort of saying it to themselves because they know it. In fact, Poe went to the theater and in a performance there was an allusion to the Raven. And he was so pleased because the whole audience got it and he he had made it. He was the observed of all observers. And it has endured as a poem in in all languages.

Speaker And what did he do with that success and why did he do it?

Speaker He built on the success and it all fell apart. He built on the success inasmuch as he published a book of tales, he published a book of poetry, and he was lionized. He was the great man.

Speaker Which, of course, from his point of view, he been all along. Finally he was recognized. He took a position with the Broadway Journal, hoping eventually to own his own publication, which was the great ambition of his life. But his drinking got in the way and he did eventually own the Broadway Journal. And he did eventually have to give it up because he couldn’t continue the work that was necessary, as Ed.

Speaker And sadly, there were also social concerns within the literati of New York City in which there were suspicions that perhaps he’d had a relationship with another woman. And I don’t believe he had, but certainly he wanted to protect Virginia. And so I think. With the various problems that he was suffering. He moved to Fordham, which was then the country to sort of recover himself and recover a calm life.

Speaker How are we doing time wise, do you have to run off, it’s five.

Speaker I’m OK, but you probably have somebody coming soon exactly like, you know, and you know, what does it how does it apply to power?

Speaker Why didn’t the power of the input, the perverse part of his notion of himself as a writer is not just as somebody who generates fabulous stories, but also somebody who has insight, somebody we would think of that today, perhaps as a psychologist, somebody who understands humanity in a way that hasn’t been recognized. So in the case of the empathy perverse, his insight was to say, you know, we don’t always do things for reasons that will improve our lives. We sometimes do things for reasons that will diminish our lives, for reasons that will hurt us. This is actually a part of man’s psyche. His argument and the impact, the perverse lays out that judgment, which you can fast forward to Freud’s death instinct and then tell stories to illustrate the way in which this functions. Would this be a reflection of his own life? Doubtless. Doubtless he would deliberately do what hurt him. Certainly the drinking is an example, but probably there are other examples where out of a sheer wish for the novel and the new, he would do the thing that didn’t serve him.

Speaker So he was he was self aware of his.

Speaker So can you just say that Paul understood himself? Paul was not always in control of himself, particularly with regard to the influence of liquor. But Paul understood his own dynamic and he understood his place in the literary world at the time.

Speaker He said, my idea of hell is being beaten by people lesser than me, which he was repeatedly, but he knew he was the man. There was no equal, except as he acknowledged authority was his equal. And had he lived longer, Melville was his equal.

Speaker He would have recognized that, so he had this particular awareness of his own strength, particularly with regard to the others in his literary world and his own debilitating weakness, and in fact, the weakness triumphs, as we know from his death, but the strength ultimately triumphed.

Speaker It’s we’re still talking about and we’re still reading him. We’re still teaching him.

Speaker Hi, Barbara. Sorry, we’re just a couple of minutes running over, but we’re almost done. I think you know each other. Yes, I did introduce you say. All right, last question.

Speaker Yeah, we’ve been dropped that last add to the whole POW mystique, the whole pole, the pole that popular culture seems to love to embrace and believe in.

Speaker Well, here’s the mystery of his death. Makes his death seem as if he wrote it, it seems like a post story which is open to endless interpretation, except it’s an actual thing that happened. I don’t think we’ll ever know the facts of the case. There was an understanding for a long time that he was couped, that he was he was brought from tavern to that tavern to vote with the promise of a drink and that he was kind of used up and thrown down and found rather the worse for wear. But there have also been many, many other explanations. I am not persuaded that he was bitten by a rabid bat, but I’m convinced that such explanations will continue endlessly because it is so fascinating. But it’s so fascinating in part because the mystery reflects his work. And so even as we think about his death, it takes us back to the work he did and to his life.

Speaker And why does he endure why, you know, he just generation after generation. What is it that he’s touching?

Speaker And I think he offers a blend of reason. And fear the reason you see in the the native tales you see in the careful craftsmanship of all his work, but at the same time there is that.

Speaker Terror fear is that morning, fear is that intense feeling that is not under rational control. And that combination, I think, speaks to us since we. But we find it reflected in ourselves, the belief in reason to hope for triumph of reason. And yet the awareness of the darkness and the emotion that is just beyond our grasp.