Speaker I was in the first class. Within the very first lesson, the way I knew about it was that I was a student at New York University and I was taking some dance classes with Martha Hill, who at that point was teaching there.

Speaker And when we started, she asked me to come. To the school, an audition to get in. So I was sort of moved over with her. And that’s really how I came to find it. I had no idea that I was even going to. Really. Do that as a career.

Speaker What was what was known to you at that time about the music school? I mean, how did Martha Hill. Where did they even decide this this sort of pre-existing, you know, grand music school that they would?

Speaker That was that was Bill Schuman’s idea. He felt that it was an appropriate thing to do. And he was the one who recruited Martha Hill. And the two of them planned this. There had never been anything like a conservatory in the United States for that. It was really a totally new idea. There was never a dance division associated with a conservatory. It was really out of whole cloth. And those few months vision that the whole thing started. And he I think he he believe very strongly that that music and dance belong together. He had written a score for Martha Graham and he was very excited about that. And he’d also written a score for the new tutor. So. And became a dance lover.

Speaker And that’s how the whole thing got started. What?

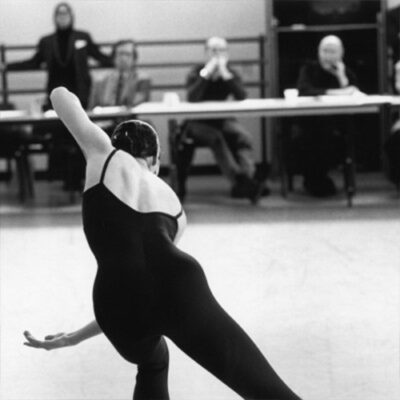

Speaker What was your audition like when she said she’d already knew you? But she said come up and audition. But like literally a panel of people would tell you about.

Speaker Oh, yes. The audition process was one in which the entire faculty or as many of them they could assemble at any one day. Oh, watched. And you had to do classes and then present a small variation of small dance. It was very scary.

Speaker I’ve never decided which side of that table it’s worse to be on. I still haven’t decided that.

Speaker And what was the school when you first got there? I mean, it’s this brand new program is everybody sort of figuring it out, as it were. Tell me about that first year.

Speaker Well, we were a very motley group because we were a group of people who of very different kinds of experiences. Some were quite experienced after. Some were fairly novices as as I was. Although I’d been studying dance, it was not totally new to me. What it was not I, I wasn’t among the chosen. It was a very difficult first year. I think it was just as difficult for the faculty as it was for the students because nothing like that had ever existed any place. There’s never been a place where a ballet faculty and modern dance faculty even spoke to each other.

Speaker In fact, mostly they didn’t speak to one another. And somehow or other, Martha Hill will wield it, welded it all into an operational hole. But the first year was quite difficult because none of the people who were teaching had ever had much to do with academe. So they really weren’t quite sure about how it functioned. And they hadn’t yet formed allegiances or collegiality, one with the other. So it was a little difficult.

Speaker But we survived. And it was a spectacular first class.

Speaker I mean, if you think about the people who were in it and what they went on to do, it’s amazing.

Speaker Well, tell me a little bit about who were these faculty? Who were these first class?

Speaker I mean, the faculty were the people who were gramme dancers like Helen Miggy and Ethel Winter. And that generation of dancers. And Anthony Tooter was the main ballet factory, along with Margaret Cresco and some of his the people that he had worked with at the Metropolitan Opera Ballet School, which formed approximately the same time a few months before. In the same year, I think the Met start in school, started in 1950 and enjoyed its first class. Was it either in the fall of 50 or or 51? I can’t call it up right now. I’m sure you can check it out. That was the ballet faculty. And Doris Humphrey was did some teaching of composition. Louis Horst was on the faculty. It was a spectacular faculty. It was it was Hanieh home, did some teaching. There are D.M. even came in and did some guest classes. She was not on the regular faculty. Robbins was supposed to teach there. But at the last minute he was doing something else and it wasn’t free. It was a lot of big names. One of the things that was kind of interesting and unusual was that Martha Hill chose to have the British School of Ballet taught instead of what was much more popular, which was the Russian school. That was controversial to start out with, and the fact that she brought ballet and modern dance together was extremely controversial at the time. Students who are the students?

Speaker Well, the woman who is now the head of the Rubin Academy in Jerusalem was a student, Rena Gluck.

Speaker Another. Well, speaking of Israeli. Another woman who is now an Israeli filmmaker whose name is a leader, Guiora was in that first class. Nancy Zackham Dorff, who was Nancy King then, was in that first class. Pina Bausch was in that class. I don’t know if Peter was there the first year or maybe the second. Try to think who else? Paul Taylor was there while I was there. It may not have been the first year. It may have been second or third. Oh. I can’t I can’t come up with any of the other names, but it was a class that went on. Oh, a man named Harry Bernstine who was who went on to be the head of the department at Delphi University and who was a writer for Dance Observer, was in that first class, Ginnette Roosevelt, who was later on the chairman of the dance department at Barnard College. Went on, several people went into the Graham company and a lot of people went into the company. In fact, the current director of the looming company is a Jewish person, although she was not. She’s much younger. It was not not first class. She was there.

Speaker Well, when I was in the faculty, it anyway was it was a class that many people went on then to be leaders in the dance world. Not only performers are not so much performers, but really leaders who then took the dance world to another step.

Speaker Why do you say that it was so controversial to bring this ballet down together in the spirit of that controversy? How did she get such heavy hitters on board? I mean, what was the intrigue and what was the controversy and then what was the intrigue for them that everybody came amidst the controversy?

Speaker The controversy was very simple. The earliest modern dance was in revolt against the classical dance, against ballet. And therefore, putting them under one roof and having dancers study both techniques was a very controversial move. You were either in the modern dance camp or the ballet camp, and the cats didn’t cross. The other thing that was controversial, as I said, was the fact that Martha chose to have the British School of ballet, the Getti school taught rather than the Russian school. That’s a little esoteric. You have to be in the field to understand the differences. But Balanchine came out of the Russian school. So that gives you some idea. And his the whole School of American Ballet, Russian influence training. And there was not. A famous big school in the Metropolitan Opera Ballet School, which had just started that taught the Italian technique to get his Italian through England anyway. So that was a controversial move. What brought them there? It’s hard to say I don’t. I don’t know what their motivation was. I think that Martha Hill was extremely prospects wasted. She had a real perspective on where the dance world was going, a very large perspective, and convince people that that was the future. And it should be the future. And, of course, she was proved quite right. Because now there’s almost nobody who studies one technique without studying the other. I think the lure of the respectability of of of a some kind of an academic position was, one, a steady salary, although they were salaries were very low. But still, I think that was attractive. I think the prestige of Juilliard was attractive. I think a little bit it was like having a home base and people were kind of floating around and they didn’t have a home base. I think that was one of the things. Also, Martha Hill had dance with Martha Graham. She had been the person who started the Bennington Festival, which was a very important. Milestone in the history of American deaths. It was the place where American modern dance really came of age. She’d started that. So she had a lot of friends in the dance world and people trusted her judgment because she’d created something that was very important. How she lured tutor a I. Can’t tell you except to say that at that point he really felt that he could no longer exist on the kind of money he was making as a choreographer and decided to go into teaching. And first he did the Metropolitan Opera Ballet School and then Juilliard. So that probably was was part of it. And it was teaching in a very different way than teaching in a studio because you had something very attractive or a teacher having the same students for four years and seeing them develop. And that does not happen in, generally speaking, in the private studio schools. So that was another kind of interesting idea. I think that’s what kept faculty there.

Speaker I think with the Graham faculty, Graham said, go, they went. That’s the way it was. It was also a way of making a living. So I think all those factors combined. How she got everybody to cooperate and and work well together is a great mystery. I tried to follow in her footsteps. And I don’t know if I did when I was the director of the dance division. We all those people together. It’s a trick.

Speaker What was what was part of the Hill like when someone was telling us the other day about seeing footage of of her, you know, opening up the trunk of her car at Bennington and everybody taking their hatboxes out on.

Speaker We’ve seen the photograph, very prim photographs of her in the office. And then a voice coach from the drama division said, wow, she had the greatest Ohio accent. I’ve tried that. Every time I get to someone is cast in a role. They’re supposed to be from Ohio. I have to think about I mean, it is a lot of memories. I mean, a lot of kind of her spirits going to vote.

Speaker But from your perspective, you can ask one question. Can someone go investigate with Marilyn estimated that really?

Speaker Because it’s a little bit about who she was, what she was like. How did she really enter into the dance? World and it come to such prominence.

Speaker Well, as you as you said, she was born in Ohio in a little town. And apparently her father was very much against her being a dancer. But he she wanted to do it so badly that he allowed it in that particular period. That was the beginning of American modern dance and.

Speaker Oh. Dancers. Oh.

Speaker It really came out of higher education. The modern dance end of things. And she apparently was able to convince her father that in some way that it was respectable because it was it respect, very respectable to be a dancer in her time.

Speaker She was quite a character. She. You talked about her voice. She had this amazingly penetrating voice. You could hear it when she wanted to say something. And you were down the hall. One hundred yards from her, you could hear her perfectly well, even if you were deaf. She is punched dead voice. When I first knew Martha Hill, I’m going to talk to you about the way she was dressed, because I think it’s it’s. Typical of the lady, when I first knew her, she wore sandals and peasant skirts and peasant blouses. By the time she was director of the dance of In a Joy, she wore a suit every day and had her hair at a little knot that we became famous because it was sort of on the side of her head. Everybody caricature that. But not so. And there was the the panorama of how she changed.

Speaker She changed from being a very sort of avant garde, loose, loose. That’s not the right word, but enterprising, interested in new things. She was being a dancer at that point, was very out of prim society. I was very surprised to hear you describe her as prim because it’s not my idea of her. But she went from that to being a very highly respected figure in the dance world and a very conjoint spokesman for the dance world and a very and she learned how to present herself in such a way that.

Speaker Well. For instance.

Speaker If you are the director of the dance division at Juilliard, you sit three or four times a year up on a platform with all men are wearing suits, and you have to somehow fit yourself into that image. And Martha Hill learned to do that was certainly not her first inclination. She’s an interesting lady. She had a long term love affair with a man who his wife was an institution and he wouldn’t divorce. And finally, finally, towards the end of her life, they were they were married for a very short time and then he died, which was kind of sad. But she adored him. So she had a fuller life than one would expect. I mean, on the outside, you think of her as this kind of spinster lady. That’s not true at all. And I remember that now when I was a student at Juilliard, I was commuting back to Philadelphia in my hometown. I was teaching for my teacher. And I kept meeting me, meeting Martha Hill on the train. And she kept hiding from me.

Speaker She kept trying to make believe she wasn’t there because she was going to see this guy left her. So and then only when she found out that I was having a love affair. Was it all right for her? Admit you. So we were friends from way back. Does that give you some kind of picture of her?

Speaker Yeah, totally. I think it’s only the photographs of those later years. Yeah. With. Yes, with the bond that with. That has drawn me to this kind of prim image. Yeah. She wasn’t the skirt and the sandals was taking it.

Speaker What was it. What was it like around the school at the very beginning. The Clairemont building. The studios. It was dreadful.

Speaker My strongest memory is having an eight nine o’clock or eight thirty in the morning point class, an international house in a dingy gym that was always cold. That’s that’s torture. That’s why I say it was dreadful, was there was really no place for us. And we used as Studios’ the orchestral, a rehearsal room and the opera rehearsal room. But we were always on borrowed territory and people were always marked the way the building was. Was that you had to go through the main studio, the the orchestra room, sometimes to get from one side of the building to the other. So there was always people there were always people tramping through. And in the beginning, they were so unused. The musicians were so unused having dances around that they would come tramping through and gawk or or mimic or just be clowns and and be very distracting for us. And there wasn’t really sufficient space. And if I have a wonderful image of that, we use the same dressing room as with as all the opera diva students. And it was so funny that the opera ladies would be putting on their makeup and primping and the dancers sticking their feet.

Speaker Let’s watch. But that was, again, adds a little incident.

Speaker But that’s typical of what was going on there, the fact that there was really no place for the dancers and they had to make do. And it was very difficult.

Speaker But we manage. We managed.

Speaker So in a sense, they sort of made this dance division, but really didn’t.

Speaker Well, they didn’t have a space for. They couldn’t. I mean, that was their building, period. It wasn’t a question of ill will. It was a question that that’s what they had to work with. And I’m sure that the the the orchestra, for instance, that was furious that they lost there’s some space, some time space was constantly a fight. Is constantly afraid I can’t speak about at absolutely at the moment, but when I was, there was still a fight spaces because for dangerous spaces, absolutely critical. The right kind of space is critical. It impinges on your learning of your skills.

Speaker There is some different people that had described her as the building with sort of like. Coat check girl.

Speaker Oh, Annie. Everybody loved it, KUCZEK Lady.

Speaker She was not a girl. She was up in years. She was a wonderful lady. She was the mother of us all. Definitely.

Speaker And what was the environment in that sense? I mean, we’ve gotten sort of like primly dressed as a lunch room like this. Apparently, there was an elevator and elevator man who were white.

Speaker Oh, I didn’t remember that. There probably was. The lunch room was a cavity. Well, I think when the dancers came in, they just shook everything up because obviously they were all we were always getting these little notes saying, please, you have to put something on over your leotard before you go to the lunchroom, before you take the elevators. I mean, we just obviously dress differently because we needed to. And it was a nuisance to get dressed in between your classes and just waste your time. The lunchroom was just a nice little cafeteria. I think in the very beginning there was very little mixing.

Speaker But that didn’t last very long. The dancers were very attractive young ladies, and that didn’t escape the view of the musicians.

Speaker So there were several marriages that came out. But first, it’s mine among them. But. Eventually, we worked it out and there were no more conflicts. But in the beginning was really very odd.

Speaker And then talk to you about these. These. You know, these sort of early teachers and people that you were studying with. I mean, Louis, Horst and Martha Graham herself teaching classes and and tutors classes in LA Mowen.

Speaker I mean I mean, a mom wasn’t played at home later. Yeah. But in in those I mean, it’s we’re talking about, you know.

Speaker The high watermark right here.

Speaker Right. Well. Tourist classes were extraordinary. The. Well, I’m doing a biography of Tudorza.

Speaker Oh, I know all about those glasses, not alone. Yeah. Yeah.

Speaker But his classes were amazing here because my voice is saying what you said. Tutors, classes. His name. Because the more that you use people’s names better to just classes were extraordinary.

Speaker He was just a most fantastic teacher. He. First of all, he had the patience to teach people. Some people were really novices in ballet. They were brought in because they were not novices and wanted us. So he and he I had my first ballet class ever from Anthony tutor. I mean, you have to be met. But he was a fabulous teacher. He just knew how to present the material in a way that. That seduced you out of your your bad habits. And he talked about movement from the inside out. He didn’t talk about poses and he made the bally material. Oh. Really live for you, in a way, he also insisted on impeccable musicality, we do sing sometimes well, we danced and all kinds of devices he used to make to make you really understand what you were doing. And that was very unusual for a ballet teacher, particularly at that point. A lot of the techniques that he used are now more or less standard, but at that time they were not at all standard. It was much more standard for somebody to come in and give a class that is to say, give a series of combinations that you did. And that was that and occasionally make a comment on them to do. Didn’t teach like that at all. He would stop the class and ask you why you thought you were doing something, what it was going to improve. Why? How it was going to affect your dancing. He was also very interested in what you did out of class, as well as what you did in class. He messed around in people’s lives, but in a very positive way. Graham work was quite aloof. She only taught on occasion. And mostly it was her. The people in her company who did the teaching. When she came in and taught, she had a profound influence. There was no question she was a very mystical kind of teacher. And she. Things were always in terms of of analogy or metaphor or poetic. And somehow or other, you got the physicality out of that. But mostly we were taught the Graham technique by the people who were in her company. And each one of them had a very different personality from the other. I remember how Alan McGee, his glasses were very difficult and she was rather impatient. Ethel’s classes were different, though she was much more of a nurturing type, but it’s kind of interesting because. Everybody reacts differently to teachers and needs a different kind of teacher. And because we had a panoply of teachers, I think it was very helpful. They sort of got got to everybody, one or the other. I’m just trying to think who who else? Louis horse classes were probably the most influential classes in terms of the growth of modern dance of anybody, because he. Was the only one who was teaching dance composition in a very structured fashion. And he was a tyrant.

Speaker Hardly ever class went by when somebody did go out of there crying.

Speaker It’s just par for the course because he really would not put up with self-indulgence. And that was a very wonderful thing because modern dance can be self-indulgent and he just wouldn’t have any of it. And we were taught very strict, structured way of going about composition. And, of course, eventually you. You abandon those kind of formalistic that kind of a formost straight jacket, but you abandon it with a lot of stuff that sticks. And without that kind of training, it’s just putting one movement after another with no logic. Every choreographer that you can think of studied with Louie, just about everyone. He was an enormous influence. He was a huge influence on Graham. And he was. He was the Graham’s mentor. There no question about that. And lover for a while.

Speaker So his classes were amazing. I learned a great deal. From his glasses.

Speaker The other thing that we that was very important to our training was very, very strong musical base. And I think that that was one of the things that was in Bill Schumann’s head, is he felt the dancers weren’t trained musically and they ought to be and may have been one of the things that made him want to bring dachas into into two year. But we had that had music class every single day, and we had the good fortune at that point early on. And then some person, Kitty, was my teacher. He was a fantastic teacher. He later on gave up teaching the dances because he said he could stand to see one more person in an Apple class. But we had a huge training in music. And it’s kind of interesting because people who came out of there went on to be opera directors. Martha Clark is one of them. And Dennis not directed opera and. Michael Toughies, these are people who graduate from their directed up, quite a few of the people have gone on to be both choreographer and upper directors. And that was an unheard of idea for somebody to be an opera director who came out of the dance world. But it was because our training was extremely rigorous. I mean, we we we had to learn. History, we had to learn. We took dictation. We did everything that a musician does with. Except that we didn’t really read music so well. But we had to learn how to read music. So I think that was a very big addition. Dancers, generally speaking, don’t learn music in that kind of depth.

Speaker We were going to you you’re just going to tell me a little bit about Mr. Miller and how she fit into this?

Speaker Well, she she we have to say her name. I just don’t know what was at that moment doing. A certain amount of kind of Americana ballets associated with American Ballet Theatre, and she came in to teach repertory classes, and I remember us learning stuff out of Rodale and various other of her dances, and that was really her role there. She was not a technical teacher and she wasn’t one that came in for every year, but she came in kind of for a guest shot series of guest shots and. She was very interested at that point and in what we mount. Now my call ethnic material or maybe we called genre material, I don’t know what the new popular word is for it, but she was very interested in. The American West, for instance, and the dancers. Square dancers and that kind of thing that happened are also of the dance material that came along with people who emigrated to the United States. And so what she was doing was really. Exploring that material and teaching us some of that material that was very, very healthy. I forgot to say that also in the very beginning, we also learned folk dance. And that was very unusual. Again, that was Martha Hill’s idea was very unusual. She just felt it. That that anybody who was going to be a dancer should have a very full scope of what they knew. It wasn’t good enough to just know a little chunk. So you needed very much to know everything there was to know about that’s possible.

Speaker And you just mentioned that the terror inducing A.I. we hear a lot about also because she was referring to fix your collar right here.

Speaker What do I do with that on this side? Just a little bit. Perfect color.

Speaker But Anna Sokolow, I mean, who we’ve heard stopped people in the hall and said this is a crime to people.

Speaker What is what is up with this woman?

Speaker Can I just tell you a wonderful story that absolutely epitomizes what she demanded of debtors? This is a story told to me by a young man in Frances Petrella, who was a student and now is a choreographer. And Frank said, well, the first time I went into Anna’s class, she said, OK, everybody lie down. Now turn over in your stomach. Reach your arms out. Reach your legs out. Now jump.

Speaker If you can imagine lying flat on your stomach. There’s no way you can jump. But that epitomizes what she. She was always demented, the impossible and mostly got it.

Speaker She was extremely exigent. But she had a kind of integrity. That is very rare to find. She. Her life was tense. Her life was really dense and it’s interesting because you talked about the mill and and the show side of things, and it did a lot of work in theater. I’m not in musicals, but in theater. She actually choreographed hair. But at the last minute, there was some difficulty and she was out and somebody else was in. But she did a huge amount of work in the theater movement for actors and. And she and her dance things were very influenced by that. They were always full of dramatic. Drama, dramatics, persona. And she somehow, as tutor did, got at the insides of somebody and sometimes got it added at that in a very destructive way. So that’s why everybody cried. But because she was able to see where your vulnerabilities were and use those vulnerabilities to help you grow. So and she was not ever satisfied with the superficial. Performance. It had to be one that came really from your gut. And G had no no reluctance about going inside of your gut and tearing it up to get what she was looking for. So I’m sure that’s what Martha Clark was talking about when she said she cried with. But a lot of people cried with them. And Anna never could figure it out. She just didn’t know what that was about. I mean, that was just the way you did things.

Speaker And early on. You know, because you were. I guess still there at that time. Back in a teaching capacity. How did it come to pass that she would sort of straddle this drama dance division in terms of teaching a lot of classes under housemen?

Speaker I mean, well, she she had a long history of teaching the neighborhood playhouse, and she taught movement for actors for many, many years. She wasn’t the movement for actors teacher. So it seemed like a natural thing. It was not something that was arranged through the school. It was arranged because Houseman admired her work and Martha Hill admired her work. So in a way, it’s accidental.

Speaker It was not that they got their heads together, say, let’s hire Adam, but they just each of them did it because of the contribution they felt she could make to the department, to each department.

Speaker And later, you were saying Paul Pillar was there as a student in your time. Yes.

Speaker And. Now, of course, his work is kind of a seminal part of them programs. But I mean, what was what was his experience there?

Speaker Are your experience to him as a as a dance student?

Speaker Paula’s character, Paul Taylor, was a character. He really was. He. He. He was it is was so tremendously gifted as a dancer as well as as a choreographer. And there in the beginning at Juilliard, of course, that’s it was as a dancer that he was being explored. He came to Juilliard. He had been a swimmer at the university at Syracuse University and had been a dancer. But he had a wonderful physique and an enormous capacity for dance. He was just really a natural dancer. My experience with him is that we were all extremely jealous because Paul could really have it the way he wanted after he was in the school, I think a year or two, couple of years, he said. I remember he he said, well. He he was going to go down, see Ozzy’s company, but. He wasn’t so sure he wanted that maybe put more distance, have to put this into context.

Speaker We were all had our tongues hanging out to even be able to audition for it. There were those companies. And he was clearly going to be accepted wherever he went.

Speaker And he was a maverick. There’s no question about it. But a fascinating maverick, very bright. He gave his first. Choreographic concert, I think, while he was at Juilliard, and he was very experimental at that point, and there was one piece. Do you know the story? There’s one piece in which the curtain open and he was in one corner. And I think it was a needed Danks, but I’m not sure if somebody else woman in another corner. And that was it. They stayed. There was a little bit like the John Cage. Three minutes and 33 seconds. Nothing happened and the curtain closed. And that was the piece because he was exploring silence. Well, there is a famous review that happened, Words in Dance Observer, which was a very important magazine. And the review started a concert of balls that Taylor. And then there was a blank white space and a signature at the end of it. But that was poor. He was really in a very experimental period of his life, and I think wonderfully so because he came out of it in was some very wise and and and beautiful ideas about that.

Speaker Really bugging me. It is.

Speaker You know, if you can, because even when you began teaching and then eventually running the division, why did Graham and Lee Môn?

Speaker And then eventually, Taylor, why did those? What is it about what are these techniques? I mean, as someone well in the know. But I mean, it is the most in the most basic way when you’re watching them. I mean, of course, you can try to do them or think about them. But why did they become to this day still this?

Speaker I don’t know whatever you would call the seed of of the training. I mean, not for that. Look, here’s the Grand Plaza settlement. The debris glasses. And you go back to Graham and then you go, you know what? What, what?

Speaker Well, life is very different for a dancer now than it was. The genesis of the gramme technique really came out of her dances. And she developed a technique so that you could perform her dances and very often in the technical class, there were sequences that came out of her dances where her dancers came from, her insides. I mean, no, nobody can predict that. But also, she began to have to really think about training the instrument. And technical training in dance is really a matter of expanding your your movement possibilities. Doing more than the average person can do and learning how to make muscles that theoretically you have no control over be controlled. Her point of view came out. What I say out of her gut, I’m talking very little, literally. I mean, the hold base is one of the bases of our technique is something called contraction release, which is literally tilting the pelvis and. And reacting in the upper body to that pelvic tilt. So it really is viscerally out of your gut, it’s not I’m not speaking poetically now when I say that. Oh, and. It the the basis for any technique about whether it’s a successful technique or not is whether it enables you to do movement that you couldn’t ordinarily do. I think that that’s a that’s what it’s all about. What the training is all about. So. How can I say it’s the seed? It was up to her once talked about the fact that he was very interested in modern dance because it developed muscles that the ballet had not yet experimented with. The Belic. Very much develops the legs and and the lower body. And learning to hold the upper body so that it balanced it out, balanced out what you were doing with the legs and feet. But there wasn’t a lot of operative body movement.

Speaker Oh, Gramps, technique had really to do with the torso. And developing that so that it became an expressive instrument as well. I think people in it who studied ballet. Use their torsos because they were gifted and they could figure that out, but it was not part of the teaching.

Speaker Have I answered your question? I know it’s a very good idea.

Speaker You’re seeing these classes about like, you know, our bills where we’re somewhat. Yeah. Yeah. I mean.

Speaker What do you do? Why? Why?

Speaker Why has this? Things sort of stayed this, you know, whatever.

Speaker Well, first of all, I don’t think you think that the technical training has stayed.

Speaker The technical training has really grown and differed very much because we’ve learned a whole lot more about anatomy than people knew in the earlier days. And what is anatomically healthy for the body that increases the movement without. Without as much danger of injury, I can’t say no danger of injury because dancers are injured all the time. So we’ve learned a lot more about not using muscles before they’re warmed up and what how to stretch more intelligently and all kinds of things. And the training has very much changed and it’s very much influenced by that. But what I think essentially you have to think about in terms of dance training is the fact that you are trying to increase the range of movement and the grasp of movement styles and the movement possibilities of the body. That’s essentially what it’s about. So in so far as. As a technique serves that need and puts it forward, then it’s a success. A successful technique. And I guess what people have found was that, for instance, the Graham technique does do that. Absolutely does it. You conquer some of the gravitational.

Speaker By the word. Some some of the Gravett Gravitational. Constraints. That the average person has by.

Speaker Developing the musculature in the pelvis, in the torso. And you increase the the ability to twist an. The range of movement were the rich space of your movement. And where your legs can go? It’s a very cogent technique, it works. It also has built in a movement style and that is not always attractive to everybody in a lot of people who don’t want to study that technique because of it.

Speaker And what was your relationship? And your impressions of his early and Pina Bausch told us that Lemon and Tooter were like two kings who had passed the.

Speaker They really did, she thinks. She wasn’t sure because she was too lowly a student to question. But there was a battle amongst the guards.

Speaker I don’t really think that’s true. I think to think that that.

Speaker Eventually, the two of them came to some kind of accommodation, one with the other. I know the tutor, eventually respected, was a good cause of things. He actually said to me.

Speaker I’m I’m not I’m not just speculating about that, particularly when Hosie died. He he he talked a little bit. About his respect for him. But I think there was there was definitely a Viking competitive spirit there.

Speaker I think there must have been some kind of also attraction. I mean, I was I was it an amazing had an amazing aura. You really did. He he. He was elegant and kind of massive and in a very stimulating way.

Speaker They definitely pass in the hallway to Kings. That’s very good. What did you ask me?

Speaker Well, I just I was asking you about about Hosain and the kind of work that he did there that you did with him. I never was his.

Speaker What was his legacy? This is Julie.

Speaker He was 18 months association with joyed, was an enormous enjoyer, was an enormous influence on him in that Martha Hill gave him space in which to work at a known company, was actually based at Juilliard for many years. It used the studios at night. And his. I don’t think that he was a great genius in terms of developing a technique. Most of the important technical things that that are were in that technique came from Humphrey da sumptuary. Mitchell was the thinker there. He was the mover. But his choreography and his his contribution to the image of the male dancer were extraordinary. I mean, there was nothing prissy about Hosie. He was a very strong presence and a very magnificent presence in terms of dance and the choreography. He did had a. Oh, particularly for the men had. Oh, very male resonance.

Speaker That is not terrifically true of the Graham. Technique. I think the grand dances.

Speaker He had he had a huge influence and his company is still one of the major companies in the world in my modern dance. Oh, the technical things he did. Came again out of his dances. But they were. I mean, I don’t think he had a great theory about how the body moved, whereas Graham did. And Doris Humphrey did.

Speaker What was it like to take a class with her?

Speaker I don’t know, I never took class with him.

Speaker We’ve heard many people say that they used to talk in a room above him. He never quite looked at you.

Speaker Well, I have an idea that I don’t know if anybody else would go along with. It’s very personal. I don’t think that either Hosie or Martha Graham, as a matter of fact, were really wonderful teachers. I know a lot of people feel that Graham was she was very inspiring. So was it was it was inspiring. But I don’t think they were wonderful teachers in my definition of a wonderful teacher, which is to help to spend your time helping the student. I don’t think either of them could come down from their eagle’s nest sufficiently to do that. I don’t feel that about Tooter, but then Tooter was never a magnificent performer. So that’s had something to do with it. I mean, he was an adequate performer, but he was never that was never his main thrust. So I think the interest in the students was passing. Was self generated in the sense that they were looking for people to be in their company and they wanted to train them good people. But I don’t think there was that kind of devotion to developing young people that, to my mind, is key to a brilliant teacher. So that’s a very personal point of view. Controversial, I’m sure.

Speaker Talk to me a little bit about the battle.

Speaker This you talked about the battle for space with the fact that Balanchine and Kirsten were actually linking Houston, were actually occupying this space. And there is a point where what’s really going to happen to the Juliar dance division with all of this? I mean, are you really sort of aware of that?

Speaker I mean, you certainly must be taking up your space, but in the move to Lincoln Center. Do you know. Do you know about that? From the from Joe Police. But I’m interested in hearing about it from from from the from the kings of the dance.

Speaker I’d be interested to hear what she told police.

Speaker He had to say to the hideous controversy between School of American Ballet and Juilliard.

Speaker And with everyone excited about the move, was the whole idea of going down to Lincoln Center. I mean, tell me what the attitude was about it. And then the controversy came to pass.

Speaker There’s a history of going down to Lincoln Center. It’s a very complex one. First of all, it was announced to the faculty 10 years before the move actually took place. And for many years there was a moratorium on raises because they were raising money for the building. So people were not overjoyed. You might imagine. But finally, when also the dance division, people were very involved with the development of the plans for the building in terms of the space for the dance division. We met with architects. I was on the faculty there. We were polled about what our needs were. We were very intimately involved in in that planning stage. We expected as a faculty to move in there to six studios. That was what was always told to us. Apparently, at the same time as that was happening, Peterman was also negotiating with the School of American Ballet. And as I understand it, his goal was really to have the School of American Ballet either replace the dance division or at least replace the ballet end of the dance division. That plan never came to fruition because I think that balancing so Christine saw no reason to be under Peterman’s thumb, but they did negotiate at the same time for space. And for many years, the School of American Ballet occupied four of the six studios. Obviously, that made the debt division faculty extremely unhappy. And there was there was no question that there was antipathy, hostility straight on how Martha Hill managed not to.

Speaker To actually give up. The dance division, I don’t know. She just hung in there by your teeth. She fought men tooth and nail. I was very shocked because when I first negotiated for for my position as director of the dance division, I found out that Martha had not even had a budget. She had to go and beg for every cent she that she didn’t have her own budget to deal with. I mean, it just was very poorly setup.

Speaker What else can I tell you about it?

Speaker It was a very unfortunate move. Everybody was duped because the people, the School of American Ballet, all long thought they were going to get the space to. So it’s not really that they came in like ogres. It wasn’t that at all. Somehow or other, there was some do double dealing there. That was very unpleasant.

Speaker How Petermann thing that was going to.

Speaker I don’t know. I think he thought one or the other thing would work and then he would talk about how he would deal with it or deal with the other one. And I think he was hedging his bets. I think he wanted the School of American Ballet, but he was never sure he was gonna get it. And therefore, he kept the debt division, jollying them along. I think it’s very it’s not accidental that the school moved in 1969 down to Lincoln Center and to the left in 71. I don’t think that’s an extra. And he left before it was 65. So it was it was a most unfortunate period in the history of the school. It just I don’t know how happened, but it did happen and it was very unpleasant. And even when I came there, which was much, much later, it was an eighty five. There was this walking on eggs feeling good between the two things, between the two entities. Which was unfortunate because there was no reason for the. And finally, when they left, because they got their their own facilities. Everybody was thrilled. I think they were very happy because they had more space, which they needed. And we were very happy. Needless to say. So it worked out fine in the end. But it was a very bad. I mean, that bad period. In fact, there was all kinds of stuff. I think Bill Schumann wrote an article in Dance magazine in which he complained about it, and that was amazing.

Speaker It’s interesting that men in I can can I go back and just say one other thing, want to replace Tudor, I mean, while I want to eat food?

Speaker But that reputation level that you would have been who he was.

Speaker So it’s again, I sight of why wouldn’t it be?

Speaker Why would men be out to eliminate tutor?

Speaker Well, there is no question that Balanchine had a bigger reputation than tutor. He was the kingpin in Bellin in the United States. Still is a certain sense. And men thought that that would add to the prestige of the school. By the way, what was going to say is when once tutor left, there was no though. Trying to think of what documents I read that said that the Jews are no longer had a belly major.

Speaker But people.

Speaker Couldn’t major in ballet. The purpose of the school was to turn out modern dancers. Which had never been the purpose, and I’m sure Martha Hill never saw that document. She never would have agreed with it. Because when we first came into the school, we had to study both equally. Then at certain point, one could major in one discipline of the other still studying. Like, if you took ballet, you would take maybe seven ballet classes a week and three or four modern dance classes. Or vice versa. But then when when a tutor left, there was no longer that split at all. And when I came into the school, I remember the woman who was in charge of fundraising saying to me, well, it is a school of modern dance. And I said, no.

Speaker Tell me about some of the challenges you faced. I mean, you mean Martha Hill had been, you know, sort of.

Speaker Well, I mean, it was there it was it was a big legacy to take over, but it was also changing times. I mean, there was a modernity that you were bringing to it, I’m sure.

Speaker Well, what would you think? Well, were you, Joan? Yeah, I think that I’m not telling tales out of school to say that when I came into the dance division, it was kind of at a low ebb. Martha Hill had been fighting this thing with Peter men and for years and years and years, and she was exhausted by it.

Speaker And.

Speaker When I came in, it was it was my my I felt my task was to rebuild it to the reputation it had once had. And that’s what I hope I did. In terms I did not want to make. Wild changes in the program, because I really believe in the same philosophy that Martha Hill did. That’s not as not a surprise, considering you felt like it was one of her babies. But I really believe very strongly that that a dancer needed to have a real education and that in so far as your discipline allows you to have a real education because it takes a lot of time and that the dancer should be well-rounded. And I know and I thought that felt that the future of dance was one in which there weren’t going to be these kind of compartments. And so I was very much in the same philosophical train as she had, although I certainly fine tune the program, somewhat made some changes and the first thing I did was put all the all the technical classes in the same time slot in the morning so that I could people could move from one class to another as as as needed. If it turned out that they needed a higher level or a level lower level, they wouldn’t be locked into a schedule that meant that they couldn’t change. So I had. I just refused to let any of the deaths just take their academics in the morning, that did not make me terrifically popular.

Speaker But that’s too bad. It wasn’t a popularity contest. And I have to say that the school went along with it. Maybe it was terrifying to them, like, oh, no. Well, I just thought, I can’t trade dances if you do. So that was that. And the other thing that I felt very strongly about was that.

Speaker A place like New York, it should be. Should serve the dance community in in the sense that it should provide an outlet for young choreographers to try their skills. And so one of the things I did was. Put in. We constantly have I have commissioned works of of people that I consider to be up and coming choreographer’s. And I was very pleased because one of them said to me that it became a badge of honor to have this territory. I was very pleased about that. I also insisted that we have musical like musical accompaniment forever. Everything. And it was interesting because you would have thought that that wouldn’t have been a problem. But I had to fight a lot of people in order to make that happen. I also tried and I think with only minimum success. To do some more integration of the dancers with the musicians that I put in, of course, for composers and choreographers, which is still going on and has produced quite a lot of interesting work and people who are collaborating once they get out of school, because I just I hated what was happening in the dance world about. Music, they weren’t using contemporary music. It was getting more and more towards rock and pop stuff, and I wasn’t very happy about that. So I was gonna do my little bit to change it. But I also tried to make a lot of connections between dance and drama and dance and music. And because of scheduling problems, I didn’t feel I was wonderfully successful at that.

Speaker You know, we started talking about some of the conflicts that you have to develop. And I’m wondering what your thoughts are in a way, to any of these divisions ever really integrate? I mean, is it always the way the music, always the king? I love it when I passed in the hallways. I see the sign saying, you know, this is a dance studio.

Speaker The players please do not, you know, sit on the floor. I mean, did did you did one I mean, without sounding too corny.

Speaker Did that did everyone always feel like this at home? I mean, was it I mean, was the power of the school from the administration up? Really this is a music school. Yes. I mean, tell me a little bit here, because as I actually said it. I mean, yeah. Yeah, yeah.

Speaker Certainly the the. I don’t think that there’s there’s ever a sense that the dance division is equal to the music division in terms of the power structure of of of of Juilliard School. Part of that is simply numbers. I mean, there’s just this maybe one hundred dancers and they’re six or seven hundred musicians. So obviously that’s always gonna happen. And also, though, all of the administrative force, it comes out the music world, not the dance world. But I think that people have made some kind of accommodation. It’s not an an equal it’s not quid pro quo, but they’ve made some kind of an accommodation. I also think this is true of the drama division as it is of the dance division, where we’re definitely Second-Class citizens in the school, but so be it.

Speaker And what what do you think that the what do you think it means? What did it mean then? Maybe what does it mean?

Speaker Now the Juilliard.

Speaker Name as a dancer. What does it signify to people? How important? Don’t touch that. Don’t touch it. We’re just hearing things. Drives me crazy. But, I mean, what is the significance of.

Speaker Of what that Juilliard thing is. What is this Juilliard mythology? I think that nowadays.

Speaker Being from Juilliard has a certain cachet. As a dancer, there are times when it had a negative cash. But I don’t think that’s true anymore. I think quite to the contrary, that. Some doors are opened for the young dancers. Because they have a two year degree or not, because they do a degree, because they come out of Juilliard and they have had that kind of training, because it’s it is a very vigorous, rigorous and well-balanced training. And I think that’s recognized, generally speaking, the dance world. But on the other hand, the dance world is the dance world. And what you do with the audition is really what counts. Your pedigree doesn’t mean all that much to you, but to the people who are auditioning you. It’s of interest, but it’s a passing interest.

Speaker And when you say it had a negative cachet at one point based on.

Speaker Well, as I said, there was a time when when there was so much controversy and fighting going on that the training suffered and the morale suffered and the kids who were coming out of it just weren’t good enough.

Speaker So it had at that point peoples that. So why why did you go to Juilliard?

Speaker Is there something important in your in your time, things that happened or things about dancer, dancer? Truly, it’s something that you feel like we haven’t gotten yet.

Speaker I think we’ve sort of covered what it’s changed a lot. I mean, I think since I left, it’s changed. And in what ways do you perceive it being different now?

Speaker I think that this is a very different philosophy about the training of the dancer with Mr. Harkavy than there was with me. I very strongly believe that you didn’t have to take anybody into the school, but once you took somebody into the school, you had an obligation to train them to get a job. And in my mind, that meant a very varied kind of training because not everybody is going to be a star with American Ballet Theatre. They’re going to be people who get into the house, a record company. There are going to be people who who go on to be actors. There are people or whatever they’re there. There’s a whole panoply of things that that we need to train people for. There are people who who graduate from our school, went into O o period.

Speaker That’s. All kinds of other things in addition to. Belly and modern dance at. A lot of the students went on to become modern dancers. There’s no question about that.

Speaker I think Mr. Mr of Harkov, his philosophy, as far as I can see in this me you’d have to ask you may feel differently, but it’s much more of the same kind of philosophy as.

Speaker The school in general, which is that they are interested in the stars and the program is much more tailored towards producing those stars and giving those stars what they need. And. Preparing the others less. In my opinion, what’s happened is that the program has been more constricted than mine was. There are as many offerings. And it’s more focused. Mine was a much more general program. So I think that’s the basic change.

Speaker And it’s part of the thoughts in your general program that the life of a dancer is limited. I mean, sometimes it’s sad. Know, you think about how long somebody can dance or how easily they can be injured.

Speaker Yes, that certainly has something to do with it. It has to do with the fact that I’ve I’m very cognizant of the fact of the people who graduate from Junior have gone on, as I said before, to to influence the dance world in administrative positions as teachers, as all kinds of things. And I think that’s all the good. I think we’re retraining statesmen. When I was there. That’s what I was about. Whether that’s any longer true, I don’t know.

Speaker I can’t. I can’t say.

Speaker I think it would actually be good if you actually said to me, just an asset simply as possible something because since I was the one that said it will be.

Speaker Thank God you’re doing so much better than I would ever imagine. But just to bring back to me this idea of the life of a dancer and what those I mean, how hard you’re working from such a young age to really have that talent.

Speaker Oh, I think one of the things that was in my mind with this kind of broader training was the fact that the life of a dancer is short. It’s it’s a sport for the young. I don’t know that I love that, but it’s a reality. And sometimes I feel like as soon as somebody becomes an artist, they’re they no longer or debts or because of the age thing. I don’t think you can be an artist at 16 so much. But one of the things I wanted very much with my program was to give this. That’s just something that they could come back to as their career as a performer waned. And actually, that’s happened in a lot of cases of the people that trained when I was there. And before under Martha Hill, very much in that they have gone on to have second and third careers. My my is an example of it, because I went on to become a note taker and then an administrator and now I’m doing writing and all of those things really. I got some kind of basis when I was a student at Juilliard, something that gave me enough to go on so that I knew how to pursue it further when I was ready to pursue it further.